Li And N Chemical Formula

Listen to an sound version of this story

Dunzhu Li used to microwave his lunch each day in a plastic container. But Li, an environmental engineer, stopped when he and his colleagues made a agonizing discovery: plastic food containers shed huge numbers of tiny specks — called microplastics — into hot water. "Nosotros were shocked," Li says. Kettles and baby bottles also shed microplastics, Li and other researchers, at Trinity College Dublin, reported last Octoberane. If parents prepare babe formula by shaking it up in hot water inside a plastic bottle, their baby might end up swallowing more than than i 1000000 microplastic particles each day, the squad calculated.

What Li and other researchers don't all the same know is whether this is unsafe. Anybody eats and inhales sand and dust, and information technology's non clear if an extra diet of plastic specks volition harm us. "Most of what you lot ingest is going to pass directly through your gut and out the other end," says Tamara Galloway, an ecotoxicologist at the University of Exeter, UK. "I recollect it is fair to say the potential take a chance might exist high," says Li, choosing his words carefully.

Researchers accept been worried most the potential harms of microplastics for about 20 years — although nigh studies have focused on the risks to marine life. Richard Thompson, a marine ecologist at the University of Plymouth, Britain, coined the term in 2004 to draw plastic particles smaller than v millimetres across, after his squad found them on British beaches. Scientists have since seen microplastics everywhere they have looked: in deep oceans; in Arctic snow and Antarctic ice; in shellfish, table salt, drinking h2o and beer; and drifting in the air or falling with rain over mountains and cities. These tiny pieces could take decades or more to degrade fully. "Information technology's almost sure that in that location is a level of exposure in but near all species," says Galloway.

Clean-up workers collect plastic pellets from the Arniston beach in Western Cape, Southward Africa. Credit: Tom Camacho/Science Photo Library

The earliest investigations of microplastics focused on microbeads plant in personal-care products, and pellets of virgin plastic that can escape before they are moulded into objects, too as on fragments that slowly erode from discarded bottles and other big debris. All these launder into rivers and oceans: in 2015, oceanographers estimated there were betwixt 15 trillion and 51 trillion microplastic particles floating in surface waters worldwide. Other sources of microplastic have since been identified: plastic specks shear off from car tyres on roads and constructed microfibres shed from habiliment, for instance. The particles blow around betwixt sea and state, then people might exist inhaling or eating plastic from any source.

From limited surveys of microplastics in the air, h2o, salt and seafood, children and adults might ingest anywhere from dozens to more than 100,000 microplastic specks each twenty-four hour period, Albert Koelmans, an environmental scientist at Wageningen University in holland, reported this March2. He and his colleagues think that in the worst cases, people might be ingesting around the mass of a credit card'due south worth of microplastic a twelvemonth.

Bottles, bags, ropes and toothbrushes: the struggle to track ocean plastics

Regulators are taking the first stride towards quantifying the take a chance to people's health — measuring exposure. This July, the California State H2o Resources Control Lath, a co-operative of the country'southward environmental protection agency, will become the world's outset regulatory authority to announce standard methods for quantifying microplastic concentrations in drinking water, with the aim of monitoring water over the next four years and publicly reporting the results.

Evaluating the effects of tiny specks of plastic on people or animals is the other half of the puzzle. This is easier said than done. More 100 laboratory studies accept exposed animals, mostly aquatic organisms, to microplastics. Simply their findings — that exposure might lead some organisms to reproduce less effectively or endure physical damage — are difficult to interpret because microplastics span many shapes, sizes and chemical compositions, and many of the studies used materials that were quite different those establish in the surroundings.

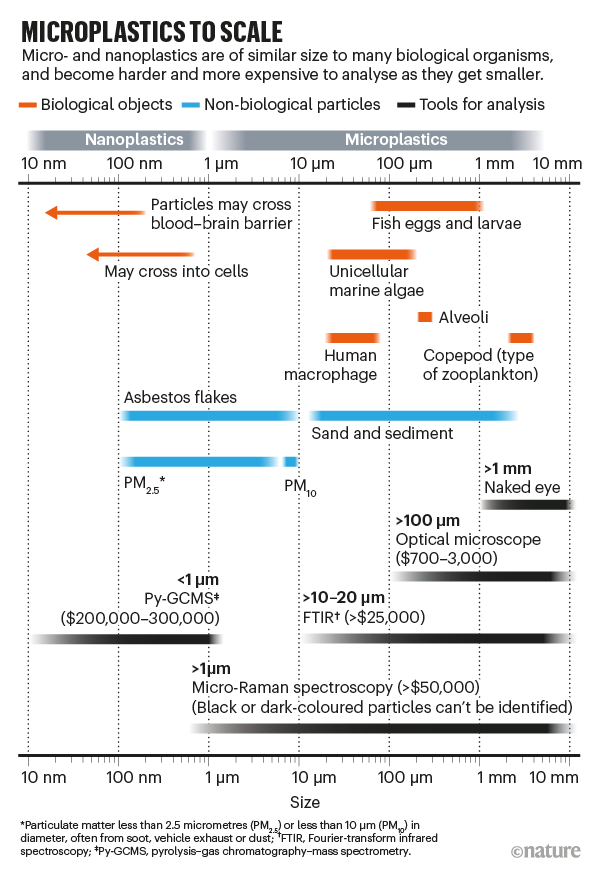

The tiniest specks, called nanoplastics — smaller than 1 micrometre — worry researchers most of all (encounter 'Microplastics to scale'). Some might be able to enter cells, potentially disrupting cellular activeness. Simply most of these particles are likewise small-scale for scientists even to see; they were not counted in Koelmans' nutrition estimates, for instance, and California will not endeavour to monitor them.

Source (tools and costs): S. Primpke et al. Appl. Spectrosc. 74, 1012–1047 (2020).

One thing is clear: the problem will merely grow. Almost 400 million tonnes of plastics are produced each year, a mass projected to more than than double by 2050. Even if all plastic product were magically stopped tomorrow, existing plastics in landfills and the environment — a mass estimated at around 5 billion tonnes — would continue degrading into tiny fragments that are impossible to collect or clean up, constantly raising microplastic levels. Koelmans calls this a "plastic time flop".

"If you enquire me about risks, I am not that frightened today," he says. "But I am a flake concerned about the future if we do nix."

Modes of damage

Researchers accept several theories about how plastic specks might be harmful. If they're small enough to enter cells or tissues, they might irritate but past being a foreign presence — as with the long, sparse fibres of asbestos, which tin inflame lung tissue and atomic number 82 to cancer. There'due south a potential parallel with air pollution: sooty specks from power plants, vehicle exhausts and woods fires called PM10 and PM2.5 — particulate matter measuring 10 µm and two.5 µm across — are known to deposit in the airways and lungs, and high concentrations can damage respiratory systems. Still, PMx levels are thousands of times higher than the concentrations at which microplastics accept been establish in air, Koelmans notes.

The larger microplastics are more probable to exert negative furnishings, if any, through chemical toxicity. Manufacturers add compounds such as plasticizers, stabilizers and pigments to plastics, and many of these substances are hazardous — for example, interfering with endocrine (hormonal) systems. Just whether ingesting microplastics significantly raises our exposure to these chemicals depends on how rapidly they move out of the plastic specks and how fast the specks travel through our bodies — factors that researchers are only starting time to study.

Microplastics collected in the San Francisco Bay surface area, labelled for study. Credit: Cole Brookson

Another idea is that microplastics in the environment might attract chemic pollutants so deliver them into animals that eat the contaminated specks. But animals ingest pollutants from nutrient and water anyway, and it'south even possible that plastic specks, if largely uncontaminated when swallowed, could aid to remove pollutants from animal guts. Researchers yet can't agree on whether pollutant-carrying microplastics are a pregnant trouble, says Jennifer Lynch, a marine biologist affiliated with the US National Institute of Standards and Technology in Gaithersburg, Maryland.

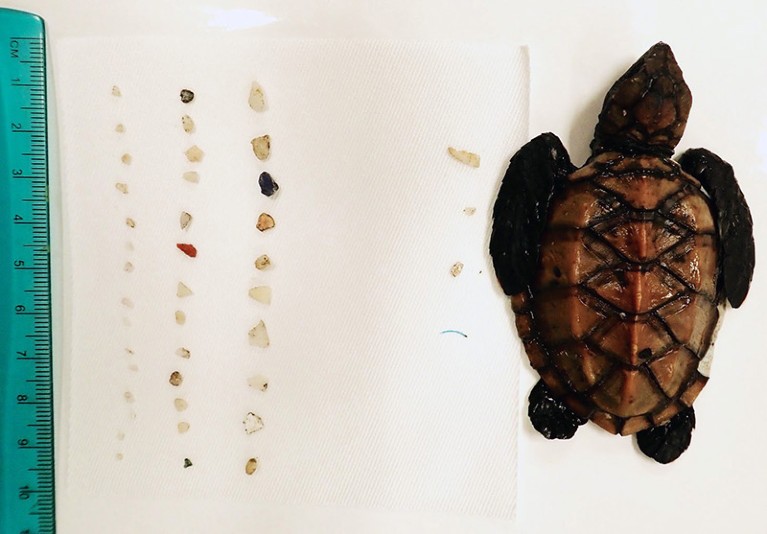

Perhaps the simplest manner of harm — when it comes to marine organisms, at least — might be that organisms swallow plastic specks of no nutritional value, and don't eat enough food to survive. Lynch, who also leads the Center for Marine Debris Research at Hawaii Pacific University in Honolulu, has autopsied body of water turtles that are found dead on beaches, looking at plastics in their guts and chemicals in their tissues. In 2020, her squad completed a set of analyses for 9 hawksbill turtle hatchlings, nether three weeks old. One hatchling, only 9 centimetres long, had 42 pieces of plastic in its alimentary canal. Most were microplastics.

A Hawaiian hawksbill sea turtle post-hatchling pictured beside its microplastic stomach contents. Credit: Jennifer Lynch

"We don't believe any of them died specifically from plastics," Lynch says. But she wonders whether the hatchlings might have struggled to abound as fast as they need to. "It's a very tough stage of life for those trivial guys."

Marine studies

Researchers have washed the most work on microplastic risks to marine organisms. Zooplankton, for instance, among the smallest marine organisms, abound more slowly and reproduce less successfully in the presence of microplastics, says Penelope Lindeque, a marine biologist at the Plymouth Marine Laboratory, Britain: the animals' eggs are smaller and less probable to hatch. Her experiments show that the reproduction issues stem from the zooplankton non eating enough nutrient3.

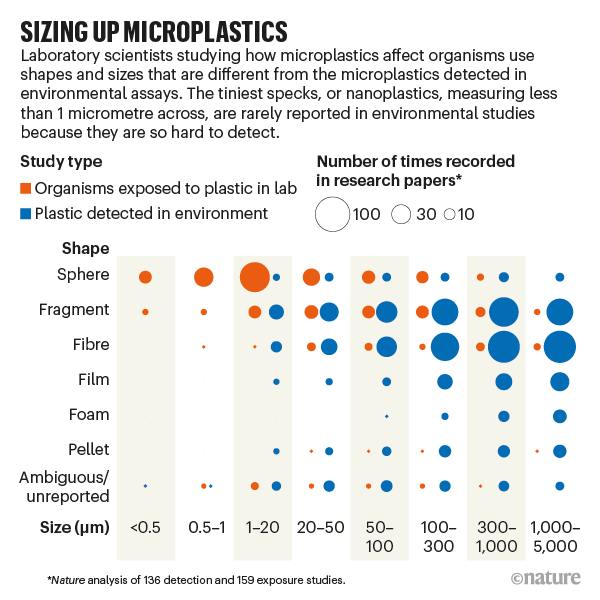

But, because ecotoxicologists started running experiments before they knew what kinds of microplastics exist in aquatic environments, they depended heavily on manufactured materials, typically using polystyrene spheres of smaller sizes and at concentrations much higher than surveys found (see 'Sizing up microplastics').

Source: Nature analysis

Scientists have started shifting to more environmentally realistic conditions and using fibres or fragments of plastics, rather than spheres. Some have started coating their test materials in chemicals that mimic biofilms, which announced to brand animals more likely to swallow microplastics.

Fibres seem to be a detail problem. Compared with spheres, fibres accept longer to laissez passer through zooplankton, Lindeque says. In 2017, Australian researchers reported that zooplankton exposed to microplastic fibres produced one-half the usual number of larvae and that the resulting adults were smaller. The fibres were not ingested, just the researchers saw that they interfered with swimming, and identified deformations in the organisms' bodiesiv. Another reportv in 2019 constitute that adult Pacific mole crabs (Emerita analoga) exposed to fibres lived shorter lives.

Red microplastic fibres wrap around a Temora copepod, a species of zooplankton. Credit: Plymouth Marine Laboratory

Nigh laboratory studies expose organisms to one type of microplastic, of a specific size, polymer and shape. In the natural surround, organisms are exposed to a mixture, says Koelmans. In 2019, he and his doctoral educatee Merel Kooi plotted the abundances of microplastics reported from 11 surveys of oceans, rivers and sediment, to build models of mixtures in aquatic environments.

Last year, the ii teamed up with colleagues to utilise this model in reckoner simulations that predict how oftentimes fish would encounter microplastics small plenty to consume, and the likelihood of eating enough specks to affect growth. The researchers found that at electric current microplastic pollution levels, fish run that take a chance at ane.5% of locations checked for microplasticsvi. Only at that place are probable to be hotspots where the risks would exist higher, says Koelmans. One possibility is the deep sea: once there, and often buried in sediment, it is unlikely the microplastics will travel elsewhere and there is no way to make clean them up.

The oceans already face many stressors, which makes Lindeque more than afraid that microplastics will further deplete zooplankton populations than that they will transfer up the food chain to attain people. "If nosotros knock out something like zooplankton, the base of operations of our marine food web, nosotros'd exist more worried about impacts on fish stocks and the ability to feed the globe'south population."

Human studies

No published study has all the same directly examined the effects of plastic specks on people, leading researchers say. The only available studies rely on laboratory experiments that expose cells or man tissues to microplastics, or use animals such every bit mice or rats. In ane report7, for example, mice fed big quantities of microplastics showed inflammation in their small-scale intestines. Mice exposed to microplastics in two studies had a lowered sperm countviii and fewer, smaller pups9, compared with control groups. Some of the in vitro studies on human cells or tissues besides suggest toxicity. But, just as with the marine studies, it'southward non clear that the concentrations used are relevant to what mice — or people — are exposed to. Virtually of the studies likewise used polystyrene spheres, which don't represent the diverseness of microplastics that people ingest. Koelmans too points out that these studies are among the first of their kind, and could finish up being outliers once there's an established torso of evidence. There are more than in vitro studies than animal studies, but researchers say they still don't know how to extrapolate the effects of solid plastic specks on tissues to possible health bug in whole animals.

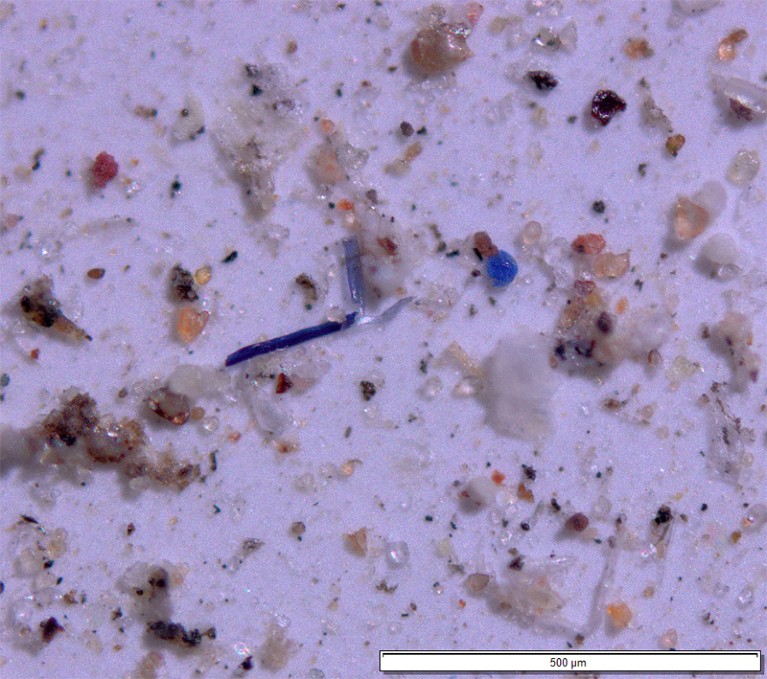

Spot the plastic? Dust, sediment, and microplastic fibres and chaplet are mingled in this millimetre-broad magnified paradigm of particles sampled from national parks and wilderness areas in the western Usa. Credit: Janice Brahney, Utah State University

1 question surrounding run a risk is whether microplastics could remain in the human body, potentially accumulating in some tissues. Studies in mice take found that microplastics around 5 µm beyond could stay in the intestines or reach the liver. Using very express data on how speedily mice excrete microplastics and the supposition that only a fraction of particles 1–x µm in size would be captivated into the trunk through the gut, Koelmans and colleagues estimate that a person might accumulate several m microplastic particles in their body over their lifetime2.

Some researchers have started to explore whether microplastics can be found in human tissue. In December, a team documented this for the first time in a study that looked at half-dozen placentas10. Researchers broke down the tissue with a chemical, then examined what was left, and ended up with 12 particles of microplastic in four of those placentas. Even so it's not incommunicable that these specks were the result of contamination when the placentas were collected or analysed, says Rolf Halden, an environmental-health engineer at Arizona Country Academy in Tempe — although he commends the researchers for their efforts to avoid contamination, which included keeping delivery wards free of plastic objects, and for showing that a control set up of blank materials taken through the same sample analysis was not contaminated. "In that location is a standing challenge of demonstrating conclusively that a given particle really originated in a tissue," he says.

Chemistry tin brand plastics sustainable – but isn't the whole solution

Those who are worried past their microplastic exposure tin reduce it, says Li. His work on kitchenware constitute that the amounts of plastic shed depend highly on temperature — which is why he's stopped microwaving food in plastic containers. To reduce issues with baby bottles, his squad suggests that parents could rinse sterilized bottles with cool water that has been boiled in non-plastic kettles, and then as to wash abroad any microplastics released during sterilization. And they can set baby formula in glass containers, filling feeding bottles after the milk has cooled. The team is now recruiting parents to volunteer samples of their babies' urine and stools for microplastic assay.

The nano fraction

Particles that are small enough to penetrate and hang effectually in tissues, or even cells, are the most worrying kind, and warrant more attention in ecology sampling, says Halden. Ane studyeleven that deliberately let pregnant mice inhale extremely tiny particles, for case, afterward found the particles in almost every organ in their fetuses. "From a risk perspective, that'south where the existent business organisation is, and that's where we need more data."

To enter cells, particles more often than not need to exist smaller than a few hundred nanometres. There was no formal definition of a nanoplastic until 2018, when French researchers proposed the upper size limit of 1 µm — tiny enough to remain dispersed through a water column where organisms can more than easily eat them, instead of sinking or floating as larger microplastics practise, says Alexandra ter Halle, an analytical chemist at Paul Sabatier University in Toulouse, French republic.

But researchers know most nothing about nanoplastics; they are invisible and cannot simply be scooped upwardly. Only measuring them has stumped scientists.

Researchers tin utilize optical microscopes and spectrometers — which distinguish between particles by their differing interactions with low-cal — to measure the length, width and chemical make-up of plastic particles down to a few micrometres. Below that scale, plastic particles get difficult to distinguish from not-plastic particles such every bit marine sediment or biological cells. "You're looking for the needle in the haystack, but the needle looks similar the hay," says Roman Lehner, a nanomaterials scientist at the Sail and Explore Association, a Swiss non-profit research group.

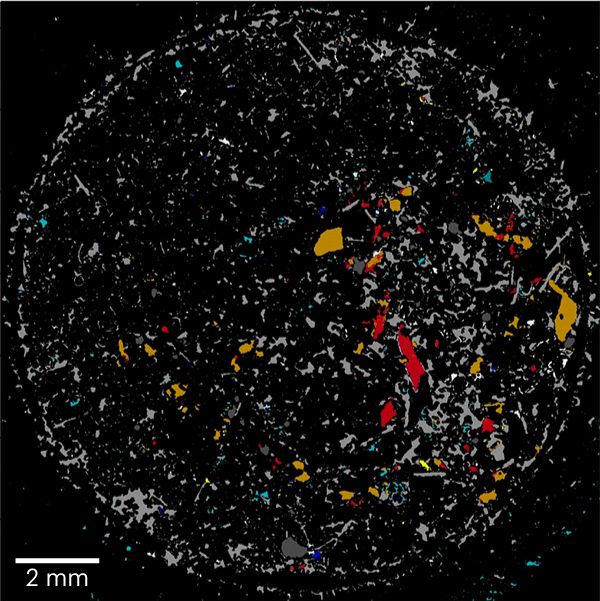

A false-colour prototype, using infrared spectrometry analysis, of a sample from a waste-water treatment plant in Oldenburg, Germany. Fragments picked out in colour are plastic polymers; other fragments include condom, soot, sand and plant fibres. Source: S. Primpke et al. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 410, 5131–5141 (2018).

In 2017, ter Halle and her colleagues proved for the get-go time that nanoplastic exists in an environmental sample: seawater collected from the Atlantic Ocean12. She extracted colloidal solids from the h2o, filtered abroad whatever particles larger than 1 µm, burnt what remained, and used a mass spectrometer — which fragments molecules and sorts the fragments by molecular weight — to confirm that plastic polymers had existed in the remnants.

That, however, gave no data on the exact sizes or shapes of the nanoplastics. Ter Halle got some idea by studying the surfaces of 2 degraded plastic containers she collected during the expedition. The peak few hundred micrometres had become crystalline and brittle, she found; she thinks that this may also be true of the nanoplastics that probably broke off from these surfacesxiii. For now, considering researchers cannot collect nanoplastics from the surroundings, those doing laboratory studies grind upward their ain plastic, expecting to get similar particles.

Tainted water: the scientists tracing thousands of fluorinated chemicals in our environment

Using home-fabricated nanoplastics has an reward: researchers can introduce tags to aid track the particles within test organisms. Lehner and colleagues prepared fluorescent nano-sized plastic particles and placed them nether tissue congenital from human being intestinal-lining cells14. The cells did absorb the particles, merely did not show signs of cytotoxicity.

Finding plastic specks lodged in intact slices of tissue — through a biopsy, for instance — and observing any pathological furnishings would be the final piece of the puzzle over microplastic risks, Lehner says. This would be "highly desirable", says Halden. Just to reach tissues, the particles would take to be very small, so both researchers think it would be very difficult to find them conclusively.

Collecting all these data will take a lot of fourth dimension. Ter Halle has collaborated with ecologists to quantify microplastic ingestion in the wild. Analysing only particles larger than 700 µm in some 800 samples of insects and fish took thousands of hours, she said. The researchers are now examining the particles in the 25–700 µm range. "This is difficult and deadening, and this is going to take a long fourth dimension to get the results," she says. To await at the smaller size range, she adds, "the effort is exponential."

A sample of plastics nerveless on 1 of Alexandra ter Halle's bounding main expeditions. Credit: Vinci Sato@ Expedition 7th Continent

No fourth dimension to lose

For the moment, levels of microplastics and nanoplastics in the environment are too low to bear upon human being health, researchers think. Merely their numbers will rise. Last September, researchers projected15 that the amount of plastic added to existing waste each year — whether carefully disposed of in sealed landfills or strewn beyond land and sea — could more than than double from 188 million tonnes in 2016 to 380 million tonnes in 2040. By then, effectually 10 meg tonnes of this could be in the grade of microplastics, the scientists estimated — a calculation that didn't include the particles continually being eroded from existing waste.

It is possible to rein in some of our plastic waste, says Winnie Lau at the Pew Charitable Trusts in Washington DC, who is the first writer on the study. The researchers institute that if every proven solution to adjourn plastic pollution were adopted in 2020 and scaled upwards equally quickly equally possible — including switching to systems of reuse, adopting alternative materials, and recycling plastic — the amount of plastic waste added could drop to 140 1000000 tonnes per yr by 2040.

Past far the biggest gains would come from cutting out plastics that are used only once and discarded. "There's no point producing things that terminal for 500 years and and so using them for twenty minutes," Galloway says. "It's a completely unsustainable style of being."

Li And N Chemical Formula,

Source: https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-021-01143-3

Posted by: gibsonyessund.blogspot.com

0 Response to "Li And N Chemical Formula"

Post a Comment